History of Television § Broadcasting

History

The invention of the television was

the work of many individuals in the late 19th century and early 20th century.

Individuals and corporations competed in various parts of the world to deliver

a device that superseded previous technology. Many were compelled to capitalize

on the invention and make profit, while some wanted to change the world through

visual and audio communication technology.[1]

The first mechanical raster scanning techniques were developed

in the 19th century for facsimile, the transmission of still images by

wire. Alexander Bain introduced the facsimile machine in 1843 to

1846. Frederick Bakewell demonstrated a working laboratory version in

1851. The first practical facsimile system, working on telegraph lines, was

developed and put into service by Giovanni Caserlli from 1856 onward.

Willoughby Smith discovered the photoconductivity of

the element selenium in 1873, laying the groundwork for the selenium

cell phototube which was used as a pickup in most mechanical scan systems.

The first demonstration of

the instantaneous transmission of images was made by a German

physicist, Ernst Ruhmer, who arranged 25 selenium cells as the picture

elements for a television receiver. In late 1909 he successfully demonstrated

in Belgium the transmission of simple images over a telephone wire from

the Palace of Justice at Brussels to the city of Liege, a distance of

115 kilometers (72 miles). This demonstration was described at the time as

"the world's first working model of television apparatus". The

limited number of elements meant his device was only capable of representing

simple geometric shapes, and the cost was very high; at a price of £15 (US$45)

per selenium cell, he estimated that a 4,000 cell system would cost £60,000

(US$180,000), and a 10,000 cell mechanism capable of reproducing "a scene

or event requiring the background of a landscape" would cost £150,000

(US$450,000). Ruhmer expressed the hope that the 1910 Brussels Exposition

Universelle et Internationale would sponsor the construction of an

advanced device with significantly more cells, as a showcase for the

exposition. However, the estimated expense of £250,000 (US$750,000) proved to

be too high.

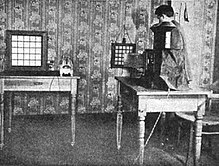

The publicity generated by Ruhmer's demonstration spurred two

French scientists, Georges Rignoux and A. Fournier in Paris, to announce

similar research that they had been conducting. A matrix of 64 selenium cells,

individually wired to a mechanical commutator, served as an electronic

retina. In the receiver, a type of Kerr cell modulated the light and a

series of variously angled mirrors attached to the edge of a rotating disc

scanned the modulated beam onto the display screen. A separate circuit

regulated synchronization. The 8x8 pixel resolution in this

proof-of-concept demonstration was just sufficient to clearly transmit

individual letters of the alphabet. An updated image was transmitted

"several times" each second.

In 1911, Boris Rosing and his student Vladimir

Zworykin created a system that used a mechanical mirror-drum scanner to

transmit, in Zworykin's words, "very crude images" over wires to the

"Braun tube" (cathode ray tube or "CRT") in the

receiver. Moving images were not possible because, in the scanner, "the

sensitivity was not enough and the selenium cell was very laggy".

Comments

Post a Comment